Back عصر النهضة الكارولنجية Arabic Каралінгскае Адраджэнне Byelorussian Каролингски Ренесанс Bulgarian Renaixement carolingi Catalan Karolínská renesance Czech Karolingisk renæssance Danish Karolingische Renaissance German Καρολίγγεια Αναγέννηση Greek Karolida renesanco Esperanto Renacimiento carolingio Spanish

The Carolingian Renaissance was the first of three medieval renaissances, a period of cultural activity in the Carolingian Empire. Charlemagne's reign led to an intellectual revival beginning in the 8th century and continuing throughout the 9th century, taking inspiration from ancient Roman and Greek culture[1] and the Christian Roman Empire of the fourth century. During this period, there was an increase of literature, writing, visual arts, architecture, music, jurisprudence, liturgical reforms, and scriptural studies. Carolingian schools were effective centers of education, and they served generations of scholars by producing editions and copies of the classics, both Christian and pagan.[2]

The movement occurred mostly during the reigns of Carolingian rulers Charlemagne and Louis the Pious. It was supported by the scholars of the Carolingian court, notably Alcuin of York.[3] Charlemagne's Admonitio generalis (789) and Epistola de litteris colendis served as manifestos. Alcuin wrote on subjects ranging from grammar and biblical exegesis to arithmetic and astronomy. He also collected rare books, which formed the nucleus of the library at York Cathedral. His enthusiasm for learning made him an effective teacher. Alcuin writes:[4][5][6]

In the morning, at the height of my powers, I sowed the seed in Britain, now in the evening when my blood is growing cold I am still sowing in France, hoping both will grow, by the grace of God, giving some the honey of the holy scriptures, making others drunk on the old wine of ancient learning

Another prominent figure in the Carolingian renaissance was Theodulf of Orléans, a refugee from the Umayyad invasion of Spain who became involved in the cultural circle at the imperial court before Charlemagne appointed him bishop of Orléans. Theodulf’s greatest contribution to learning was his scholarly edition of the Vulgate Bible, drawing on manuscripts from Spain, Italy, and Gaul, and even the original Hebrew.[7]

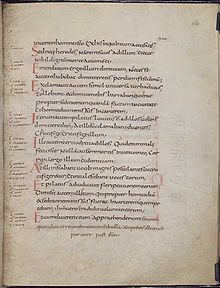

The effects of this cultural revival were mostly limited to a small group of court literati.[1] According to John Contreni, "it had a spectacular effect on education and culture in Francia, a debatable effect on artistic endeavors, and an unmeasurable effect on what mattered most to the Carolingians, the moral regeneration of society".[8][9] The secular and ecclesiastical leaders of the Carolingian Renaissance made efforts to write better Latin, to copy and preserve patristic and classical texts, and to develop a more legible, classicizing script, with clearly distinct capital and minuscule letters. It was the Carolingian minuscule that Renaissance humanists took to be Roman and employed as humanist minuscule, from which has developed early modern Italic script. They also applied rational ideas to social issues for the first time in centuries, providing a common language and writing style that enabled communication throughout most of Europe.

- ^ a b Rietbergen, P. J. A. N. (2000). A Short History of the Netherlands: From Prehistory to the Present Day (4th ed.). Amersfoort: Bekking. p. 29. ISBN 90-6109-440-2. OCLC 52849131.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. 2005. pp. 290–291. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- ^ Trompf (1973).

- ^ "Alcuin - Biography".

- ^ Tried by Fire: The Story of Christianity's First Thousand Years. Thomas Nelson. 22 March 2016. p. 325. ISBN 978-0-7180-1871-9.

- ^ The Art of Mathematics – Take Two: Tea Time in Cambridge. Cambridge University Press. 30 June 2022. p. 300. ISBN 978-1-108-97642-8.

- ^ The Oxford Dictionary of the Christian Church. Oxford University Press. 2005. p. 1603. ISBN 978-0-19-280290-3.

- ^ Contreni (1984), p. 59.

- ^ Nelson (1986).

© MMXXIII Rich X Search. We shall prevail. All rights reserved. Rich X Search